HD History

HD is named after George Huntington, an American physician who described the disease in 1872. His description was based on observations of HD-affected families from the village of East Hampton, Long Island, New York (USA), where Dr Huntington lived and worked. HD was known as Huntington’s chorea and Saint Vitus’s dance in the past.

Symptoms & Disease Progression

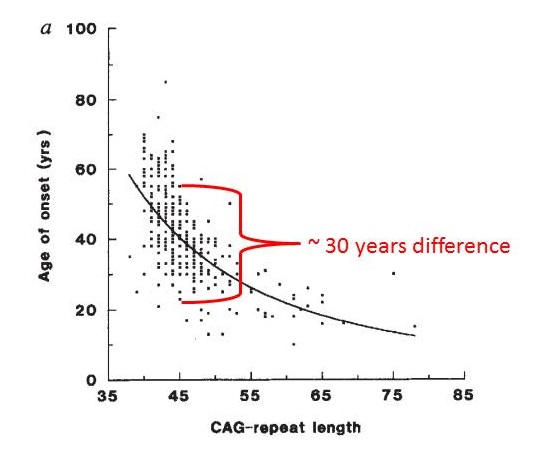

HD is a rare disease that affects 5 to 10 per 100,000 people in the European population. A similar prevalence is found in countries whose populations are primarily of European descent, such as the USA. HD is less common in Asian and African countries, where the prevalence has been estimated at 1 per 100,000 people. Men and women are equally likely to inherit the HD expansion and to develop the disease. HD is characterised by a combination of motor (movement), behavioural (for example mood) and cognitive (for example understanding) disturbances, but other symptoms may also be reported. The symptoms of HD may vary in severity, age at onset and rate of progression from individual to individual – even between members of the same family. One person may have a very obvious movement disorder, but only mild behavioural symptoms and cognitive deterioration, while another may suffer from depression and anxiety for years before showing any abnormal movements. The onset of HD is described as ‘insidious’, since it is usually difficult to determine a date when it actually starts. Most individuals who carry the HD expansion develop symptoms in mid-adult life – that is, between 35 and 55 years of age. Approximately 10% do so before the age of 20 (they have juvenile HD) and another 10% after the age of 55. In general, HD develops very gradually, so that it may go undiagnosed for many years. On average, disease duration is 15 to 20 years from diagnosis, but this varies between individuals and can also depend on the quality of care that the patient receives. The determinants of age at onset are complex and the subject of ongoing investigations. When looking at large groups of HD patients, scientists find a correlation between the trinucleotide repeat number and the age at onset of symptoms (figure below). This means that, in general, the higher the number of CAG repeats, the earlier the onset of symptoms (figure below). However, for any given CAG repeat number, the variability in age at onset may be up to 30 years, as shown in the figure below. This is probably due to the effects of genes other than HTT (so-called genetic modifiers), and to environmental factors such as lifestyle and diet. Taking this altogether, it’s very difficult to accurately predict the precise age at onset in any given person carrying the HD expansion. According to a classification developed by neurologist and HD specialist Ira Shoulson of Georgetown University in the USA, the progression of HD can be divided into five stages: The Huntington’s Disease Integrated Staging System (HD-ISS) is a biologically and evidence-based framework developed by Sarah Tabrizi of University College London (UK) and colleagues to help progress pharmaceutical research. The four stages of the HD-ISS (0 to 3) aim to objectively describe the trajectory of HD over the lifespan, starting from birth. It is hoped that the HD-ISS will allow evaluation of new therapeutic approaches in the very early stages of HD, even before clinical signs are apparent. In facilitating early stage HD research, the potential for new treatments and interventions to slow disease progression and increase clinical benefit is maximised. When HD starts early in life (before the age of 20), involuntary movements (chorea) are less prominent as a symptom than slowness of movement (bradykinesia) and stiffness (dystonia). Early features of juvenile HD include marked behavioural changes, difficulties with learning and speech, and decline in performance at school. Epileptic seizures are occasionally reported, being more common in young patients. In general, the juvenile form of the disease progresses more rapidly than the adult form. When HD starts late in life, chorea tends to be a more prominent sign than slowness or stiffness. In such cases, it is likely to be more difficult to establish a family history, because the individual’s parents may already have died, perhaps before they themselves showed signs of the disease People with HD do not die as a direct result of the disease, but rather from medical problems that arise as a result of the body’s weakened condition. These include pneumonia (which accounts for one third of all deaths in HD patients), choking, heart failure, head injury as a result of falls, and nutritional deficiencies. Suicide risk is notably increased, accounting for up to 7% of all patient deaths.How Common is HD?

What are the symptoms of HD?

The motor signs of HD are a mixture of chorea, bradykinesia and dystonia, which notably affect posture, balance and gait. Chorea comes from the Greek word choreia, which means dance and refers to the involuntary movements often seen in HD. Having trouble initiating voluntary movements (bradykinesia), and sustained muscle contractions that cause abnormal postures and torsions or twisting (dystonia), are other common motor signs in HD. Oculomotor (eye movement) abnormalities and difficulties with swallowing are also common, and speech becomes more slurred over time.

The most common psychiatric symptoms of HD are apathy, anxiety, depression, irritability, outbursts of anger, impulsiveness, obsessive-compulsive behaviours, sleep disturbances and social withdrawal. More rarely, mania and schizophrenia – including delusions (false beliefs) and hallucinations (seeing, hearing or feeling things that do not really exist) – have been reported. Affected individuals may experience suicidal thoughts, especially in early stages of the disease. Most HD patients and their carers perceive the behavioural symptoms to be more distressing than the motor or cognitive impairments caused by the disease.

HD is characterised by the gradual impairment of comprehension, reasoning, judgement and memory. Cognitive symptoms include slower thinking and difficulty concentrating, organising, planning, making decisions and answering questions, as well as short-term memory and problem-solving deficits and an impaired ability to absorb and understand new information.

There are a number of other changes that may occur during the course of HD, including loss of appetite, weight loss, loss of self-esteem, loss of sex drive, and urinary and fecal incontinence.When do HD symptoms appear?

What determines age at symptom onset?

What are the different stages of HD progression?

Do the symptoms of juvenile HD differ from those of the adult form?

What are the symptoms when HD starts late in life?

Causes of death

Diagnosis & Treatment

HD is diagnosed by a combination of clinical assessments and a genetic test. Clinical diagnosis is based on a person’s medical and family history, as well as on standard examinations that make use of clinical rating scales to assess the frequency and severity of the symptoms of HD. The results of the clinical diagnosis are usually confirmed by genetic screening for the HTT expansion (known as diagnostic or confirmatory genetic testing). If a person does not show any symptoms, but is at risk of the disease, asymptomatic genetic testing (known as predictive genetic testing) will determine whether or not they carry the expansion.How is HD diagnosed?

The clinical assessment tools used to diagnose HD and measure aspects of the presentation are not the same in all clinics in all countries. However, the tool most commonly used is the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS), which is divided into motor, behavioural, cognitive and functional sub-sections. In addition, the Problem Behaviours Assessment for Huntington’s Disease (PBA) is often used for assessing the severity and frequency of behavioural abnormalities (such as depressed mood, apathy and irritability), while a variety of tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale are used to supplement the sub-section of the UHDRS that assesses cognitive impairments.What clinical assessment tools are used to diagnose HD?

Living with the knowledge that you are at risk of HD can be very worrying. You may feel that you would prefer to know for certain if you are carrying the expansion. In that case, genetic counselling and psychological support are highly recommended, because they allow you to explore your options and to discuss your concerns. In general, predictive testing is not recommended for those younger than 18 – the age at which, it is hoped, a person has the maturity to cope with the awareness that they carry the expansion. In exceptional cases, however, it may be deemed reasonable to perform the confirmatory genetic test in children – if they show signs of juvenile HD, for example – or in women younger than 18 if they are pregnant. If you decide to get tested, a blood sample will be taken from a vein in your arm and your DNA will be extracted from it in the lab. Depending on the local service, the result will be ready in two-to-eight weeks. Guidelines for the predictive genetic testing procedure were updated by the EHDN Genetic Testing and Counselling Working Group in 2012.What is the procedure for predictive genetic testing?

The genetic test determines the number of CAG repeats in the HTT gene. The test can reveal whether you carry the HD expansion, but it cannot ascertain when the disease will begin, how rapidly it will progress, or which symptoms you might develop. The genetic test for HD is considered to be close to 100% accurate. The results from the DNA analysis are usually double-checked using two separate blood samples. In addition, blood from a parent of the affected person (or, if that is not available, from another family member) may also be tested to provide confirmation of the original diagnosis.What does the genetic test detect?

Yes. This can be achieved using a modern diagnostic procedure called pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) – also known as embryo screening – that is used in combination with in vitro fertilisation (IVF), and involves screening embryos prior to their implantation in the womb. The technique ensures that only embryos inheriting normal copies of the gene are implanted. Hence, even if one of them carries the HD mutation, PGD makes it possible for a couple to conceive a child that does not carry the mutant HTT gene, – regardless of whether the carrier is the man or the woman. However, PGD is not permitted in some countries under embryo protection laws, and it is also important to note that the chances of a pregnancy coming to term after PGD/IVF are lower than in the case of “natural” conception. In some countries it is possible to test unborn foetuses that were conceived naturally, and to choose abortion once the foetus’ genetic status is known.Is it possible for a person who carries the HD expansion

to ensure that they do not pass HD on to their child?

Prenatal (before birth) diagnosis is only available when those requesting it can show that their case fulfils certain medical and legal criteria, which are country-specific. There are two standard procedures for prenatal diagnosis. The first is amniocentesis (also called the amniotic fluid test), in which amniotic fluid containing fetal cells is collected via a needle inserted through the mother’s abdominal wall, usually after the 14th week of pregnancy. The second is chorionic villus sampling, which involves the collection of a sample of the chorionic villi (placental tissue) and can be conducted earlier – between the 10th and 13th weeks of pregnancy. It is, however, riskier for the foetus.May I test my unborn child?

There are currently no therapies that can effectively treat the underlying causes of HD. However, basic and clinical research has dramatically increased our knowledge of HD in recent years, and many studies are now underway that are investigating its pathogenesis, with a view to identifying drugs that will postpone disease onset or slow its progression. Treatments are already available that alleviate certain symptoms of the disease (symptomatic treatments), and so improve patients’ quality of life. These are divided into pharmacological (drug) and non-pharmacological (non-drug) treatments.Are there any treatments for HD?

Chorea, bradykinesia, irritability, apathy, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances have all been reported to be the most distressing symptoms of HD. There are several options for managing these symptoms using drugs. However, many medicines can cause side effects, and some may counteract the therapeutic effects of others. In addition, the same medication may have different effects in different individuals. Treatment must be personalised by an experienced HD specialist, according to the patient’s symptoms and his or her response to the drugs in question.What are the pharmacological options for treating HD symptoms?

Non-pharmacological treatments (such as psychotherapy, and cognitive, physical, speech, respiratory and occupational therapies) may improve the psychological and physical symptoms of HD. For instance, improvements have been reported in mood, motor control, speech, balance, swallowing and gait after these therapies. It is well known that physical exercise improves both physical and mental health, enhancing general wellbeing, and exercise has been shown to alleviate the symptoms of depression. There is accumulating evidence that it may also help slow the progression of the movement impairment in HD. For example, some physiotherapy programmes have been shown to result in benefits in terms of motor symptoms, gait and balance. The EHDN Physiotherapy Working Group has published a guidance document for physiotherapists working with HD patients.How can non-pharmacological treatments help?

The benefits of a diet rich in vitamins, co-enzymes and other compounds have been the subject of much discussion, but remain to be proven clinically. However, as weight loss is a problem for some HD patients, especially in the later stages of the disease, it is important to ensure a healthy diet throughout the course of the disease. At later stages a high-calorie diet may become necessary. Referral to a dietician may be helpful.Can a special diet alleviate the symptoms of HD?

Inheritance & What Causes HD

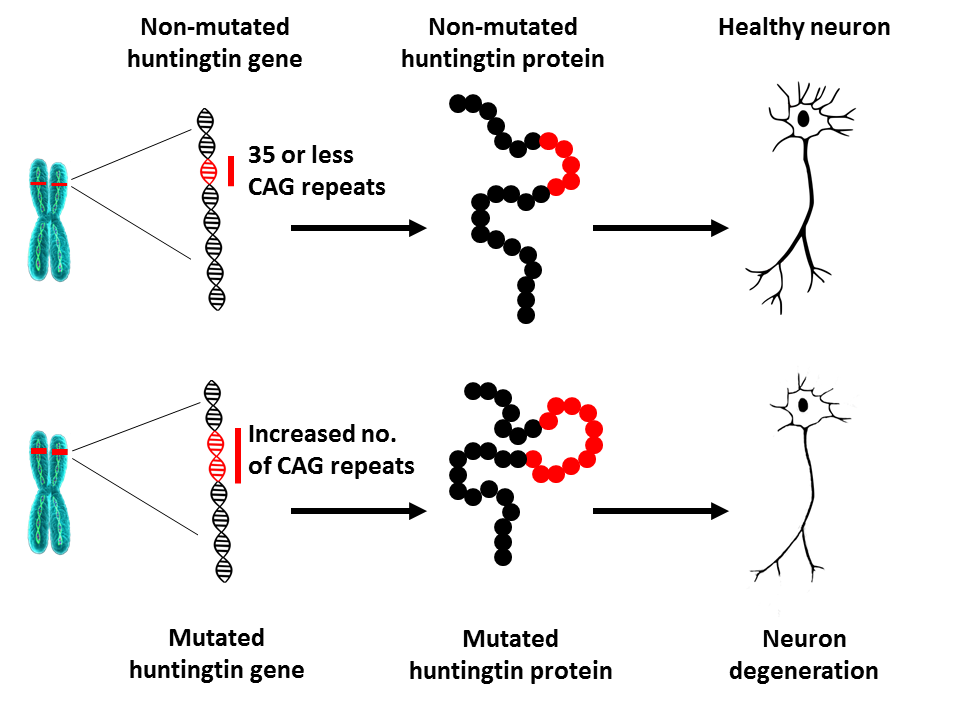

HD is caused by a change (an expansion) in the gene (HTT) that encodes a protein called huntingtin. As a result of this expansion, the gene is translated into an altered form of the protein, something that results in the malfunction and death of nerve cells (neurons) in specific areas of the brain. The exact mechanisms of the disease are multifaceted and highly complex, in agreement with the multiple functions of the huntingtin protein. Researchers are working on getting a better understanding of the underlying disease causing mechanisms to develop disease modifying therapies.What causes HD?

In 1993, scientists identified the mutation that causes HD. The HTT gene is located on chromosome 4 and encodes a protein called huntingtin. The gene contains a sequence of three nucleotides (the basic units of DNA), cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG), that is repeated several times. This so-called trinucleotide repeat can vary in length. If a person has 40 CAG repeats or more in one copy of the HTT gene, s/he will develop HD within a normal lifespan – that is, in mid-adult life. Since the expansion that causes HD is present in all cells of the body from conception, and can be passed on to subsequent generations, HD is a hereditary disease.What is the underlying cause of HD?

As the number of CAG repeats increases, that particular section of DNA becomes more unstable. This means that the number of repeats in this section can increase or decrease when it is passed down to the next generation. As long as the number of CAG repeats in the HTT gene is lower than 27, the section is stable. If the number of repeats is between 27 and 35 (the so-called intermediate repeat length), that individual will not develop HD and the section is considered normal. However, a CAG repeat number of 27 or more is unstable and liable to increase when passed on to the next generation, meaning that those children carry a risk of developing HD. Individuals with a CAG repeat number between 36 and 39 may develop HD, but only very late in life, if at all. This is known as the reduced-penetrance repeat length range. When the number of CAG repeats is higher than 39, a person will develop HD within a normal lifespan – most often in mid-adult life. In rare cases the CAG expansion can be exceptionally long, leading to disease onset in adolescence or childhood (juvenile HD). Patients who develop the disease before the age of 10 often have more than 80 CAG repeats.

What does the length of the HTT CAG repeat mean?

CAG repeat length Disease causing? Consequences for offspring? Name

Below 27 No None Normal repeat length

27 - 35 No Repeats of 27 and more can be unstable and might increase when passed on to offspring Intermediate repeat length

36 - 39 Maybe Yes, offspring have a 50% probability of inheriting the expanded gene Reduced penetrance repeat length

40 and above Yes Yes, offspring have a 50% probability of inheriting the expanded gene Fully penetrant repeat length

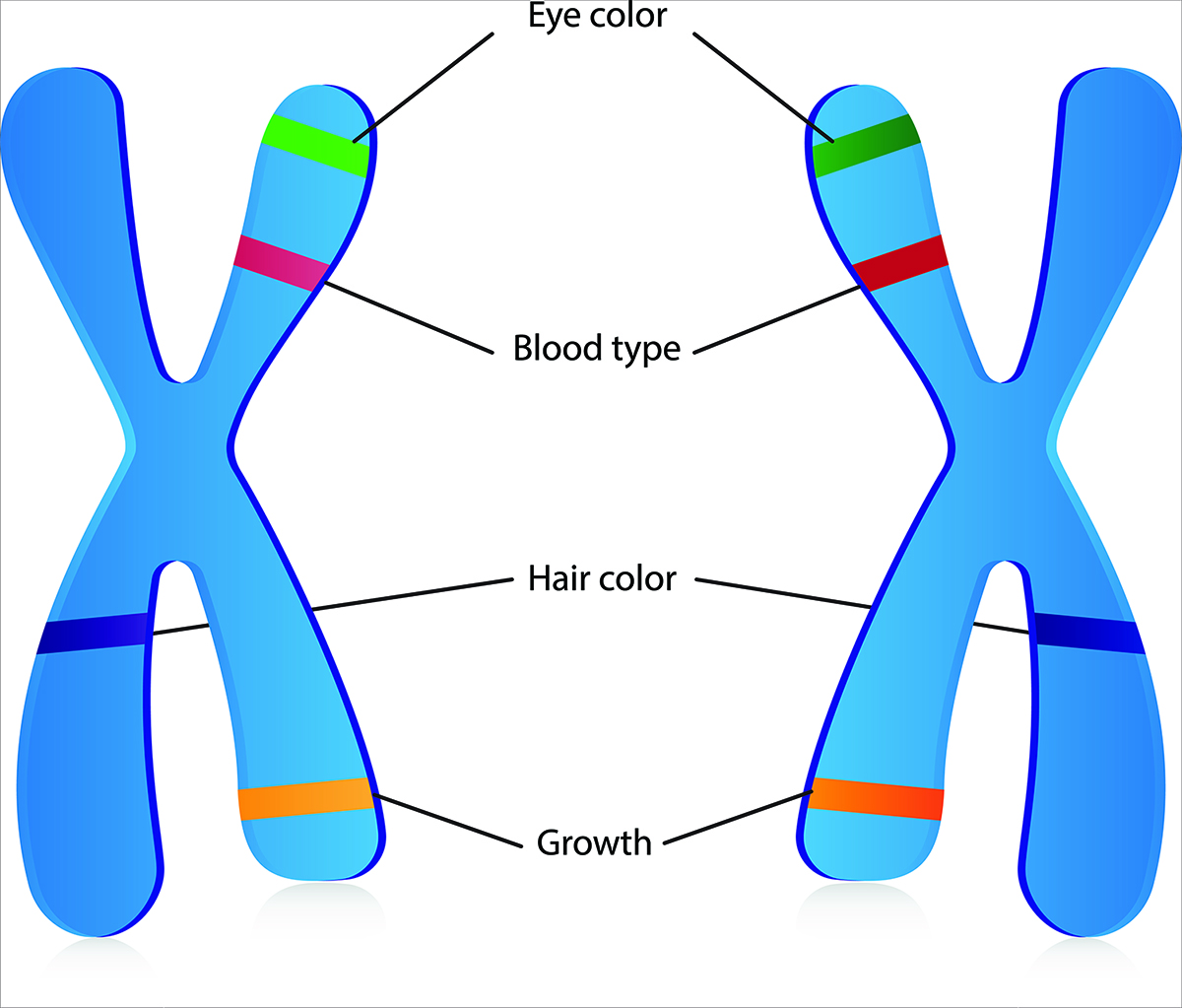

Genes are found on our chromosomes inside every cell in our body. A gene is a stretch of DNA that contains the code for a particular protein; the DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), which is then translated into the protein. Most usually, everyone inherits two copies of each gene – one from the mother, one from the father. In HD the important gene is the HTT gene, which encodes the huntingtin protein. When a child inherits an expanded version of the HTT gene then that child will also develop HD. The parent himself may already have the disease or this can develop later in age.What is a gene?

Proteins are large molecules made up of building blocks called amino acids. The exact sequence of amino acids in a particular protein is determined by the DNA sequence of the corresponding gene. Genes therefore function as blueprints – sets of instructions to cells that tell them how to build specific proteins. The HTT gene contains instructions on how to build the huntingtin protein. Proteins are the molecules that do the work inside cells – they perform a large number of essential processes, such as enzyme reactions or structural support. If a protein functions abnormally or is missing due to an expansion in the gene that encodes it, then it can affect the cell and, ultimately, the whole organism, sometimes causing disease.What is a protein?

The huntingtin protein is a very large protein that is made or “expressed” to varying degrees in every cell of the human body; the highest levels are found in the brain. Huntingtin seems to be a very important protein because the absence of it is lethal to mouse embryos. At one particular end of the huntingtin protein there is a stretch of repeats of one particular amino acid called glutamine. This distinctive feature, known as the polyglutamine repeat, normally consists of up to 35 glutamine units. In people who carry the HD expansion, however, it contains at least 36 repeats and it is this polyglutamine expansion that results in a protein that malfunctions.The huntingtin protein

HD is a dominant hereditary disease. This means that a person born with one copy of the mutant HTT gene will develop HD even though s/he is also carrying a normal copy of the gene. An HD expansion carrier, whether symptomatic or not, can pass on either a normal or a mutant copy of the gene with a 50% probability of each (provided that s/he only carries the expansion on one of the two copies of the HTT gene). Medical techniques can ensure that an affected individual only passes on the normal HTT gene to his or her children. On the other hand, a person who has not inherited the mutant HTT gene will not develop the disease, and his or her children will not be at risk of it either. The HD expansion cannot skip a generation. However, it can happen that an expansion carrier dies before showing symptoms, and that his or her children do not realise they are at risk of developing the disease.How is HD passed on?

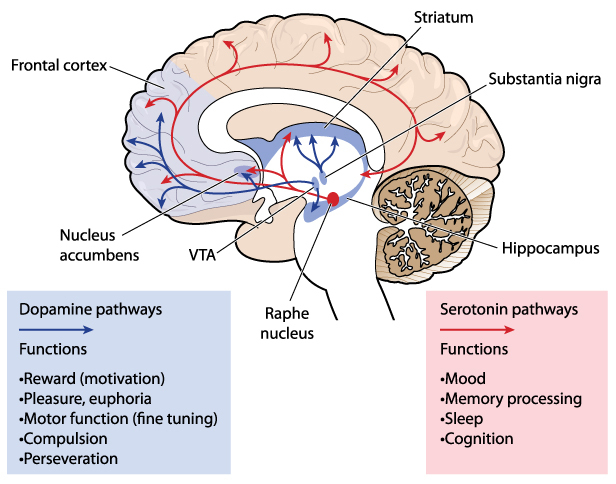

Certain functions of the brain such as the ability to move, think and talk gradually deteriorate in HD as crucial nerve cells become damaged and die. The part of the brain most affected by HD is the striatum, which is a component of the basal ganglia and located deep in the brain’s central region. The striatum is primarily involved in planning and controlling movements, but also in many other processes, including cognition and emotions. As HD progresses, it affects the cortex (the outermost wrinkled part of the brain), contributing to cognitive deterioration. In general, HD causes atrophy of the whole brain over time, impairing the individual’s general functional capacity.Brain areas involved in HD

HD In Daily Life

Testing positive for the HD expansion may affect many different aspects of a person’s life, including the decision as to whether or not to have children, planning for the future, rethinking priorities, negotiating appropriate housing, and informing other family members that they too may be at risk of the disease. Young adults in particular may need to consider the implications of a positive test result for their education, training and employment. As the disease progresses, it gradually affects a person’s ability to live independently. Working, social life and general daily activities become problematic, and patients become increasingly dependent on help from relatives and health and social care professionals. Local patient advocacy groups and clinical centres can be contacted at any time, and will provide support.How does HD affect daily life?

Efficient strategies for coping with HD have to be personalised and depend on the affected person, the stage of the disease and the family context. HD develops very slowly, so that in general there is time to adapt to the changes it brings about. For carers and loved ones, a better understanding of the behavioural and cognitive impairments associated with the disease may help them to develop strategies for accommodating these changes and maintaining a good relationship with the affected person. Helpful information and advice is available from HD specialists and patient advocacy groups.Are there any strategies for coping better with HD?

How do I contact the EHDN?

This differs from one European country to another but most often you need to obtain a referral from your general practitioner before you can see a specialist doctor. You can contact your local EHDN language coordinator who will help you.How do I get an appointment with a specialist?

Independent advice about HD can be obtained from the patient advocacy groups in your country.Is there any way I can speak to a specialist without attending a clinic?

The EHDN plays a key role in the worldwide clinical study Enroll-HD. It is an observational study that does not involve intervention. This means that it does not test experimental therapies per se. Any member of a family affected by HD can take part in Enroll-HD including unaffected companions. The Enroll-HD participants undergo clinical assessments during their annual visits and HD mutation carriers may be eligible to take part in clinical trials of symptomatic or disease-modifying treatments as and when these become available. Enroll-HD is accessible via many HD study sites around the world. To find out whether there is a site near you, please look here or approach your EHDN language coordinator, who will be able to inform you about research activities in your region. Your local patient advocacy group(s) will be able to provide you with general information about participating in research. For more information about HD research, please look here or visit the HDBuzz webpage with HD research news written by HD researchers in lay language and translated into most languages.How do I become involved in HD research?

Yes, a number of patient advocacy groups provide support for individuals and families affected by HD. These can be contacted via your general practitioner or HD specialist or you can contact them directly. The European Huntington’s disease Association (EHA) keeps a list of patient advocacy groups that might be useful for you.Are there support groups that specialise in HD?

For any other questions, please contact your EHDN language coordinator or your local patient advocacy group.

April, 2024